Headline: The Rising Economic Burden of Sciatica in Zimbabwe: A Silent Crisis Impacting Workforce Productivity

Sciatica—a debilitating condition involving compression and damage to the body's largest nerve—is emerging as a critical yet under-reported public health and economic issue in Zimbabwe. Characterized by severe pain radiating from the lower back down the leg, often described locally as "kunokorwa tsoka" or "kutsoka kunorwadza," its prevalence is climbing, directly impacting national productivity, healthcare costs, and individual livelihoods. The condition’s strong links to occupational hazards and diabetes, a growing national health threat, are creating a complex challenge for the country's strained medical and economic systems.

The Condition and Its Direct Human Cost

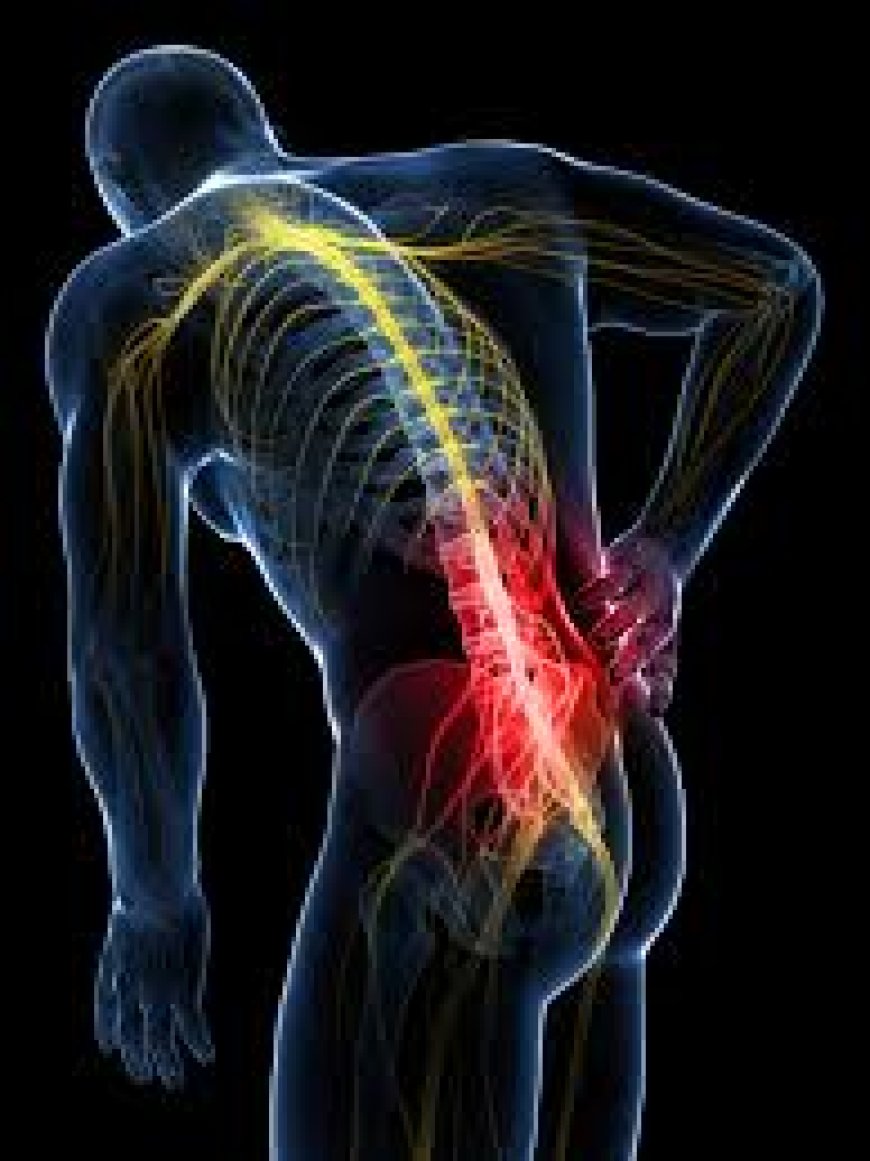

Sciatica is not merely back pain. It is a specific syndrome resulting from irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve, which runs from the lower spine through the buttock and down each leg. This compression is most frequently caused by a herniated or "slipped" disc in the lumbar spine, where the soft inner material of a spinal disc protrudes and presses on the nerve root. Other primary causes include spinal stenosis (abnormal narrowing of the spinal canal) and spondylolisthesis (where one vertebra slips out of place onto another).

For patients, the experience is often agonizing and immobilizing. Core symptoms extend beyond localized lower back pain to include sharp, burning, or electric shock-like sensations that shoot down the buttock and leg. This can be accompanied by numbness, tingling ("pins and needles"), and muscle weakness in the affected limb. In severe, albeit rare, cases involving cauda equina syndrome—where nerve compression affects bowel and bladder function—it constitutes a surgical emergency. The pain is frequently exacerbated by prolonged sitting, a staple of many modern and informal sector jobs, turning daily work into a constant struggle.

The Zimbabwe-Specific Drivers: Occupation, Access, and Diabetes

The epidemiology of sciatica in Zimbabwe is shaped by distinct local factors. Occupational hazards are a primary driver. Professions involving heavy manual labour—such as mining, agriculture, and construction—place immense repetitive stress on the spine, significantly elevating the risk of disc herniation. Conversely, the growth of the service sector and digital economy has increased sedentary behaviours, with prolonged sitting weakening core musculature that supports the spine, creating another pathway to injury.

However, a critical and often underemphasized driver is the nation’s growing diabetes epidemic. Diabetes mellitus can lead to diabetic neuropathy, a form of nerve damage that makes the sciatic nerve more susceptible to compression and injury. Furthermore, chronic high blood sugar can accelerate the degeneration of spinal discs and joints, compounding the risk. The colloquial association of leg pain with "kunokorwa tsoka" often misses this crucial medical link, potentially delaying correct diagnosis and targeted management of the underlying metabolic condition.

Compounding the problem is a severe diagnostic and specialist gap. Access to advanced diagnostic tools like MRI scans, essential for visualizing soft tissue nerve compression, is limited to major urban centres and is prohibitively expensive for most. The chronic shortage of specialist neurologists, neurosurgeons, and physiotherapists creates long waiting times, forcing many to rely on general practitioners or informal pain management strategies that fail to address the root cause.

The Treatment Landscape and Economic Ripple Effects

Treatment follows a stepped model, beginning with conservative management. This includes a short course of anti-inflammatory medications, targeted physiotherapy focusing on core strengthening and nerve gliding exercises, and activity modification. When conservative measures fail after 6-12 weeks and severe pain or neurological deficit persists, interventional procedures like epidural steroid injections may be considered to reduce inflammation around the nerve.

Surgical intervention, such as a microdiscectomy to remove the portion of a herniated disc pressing on the nerve, is reserved for cases with progressive weakness or those unresponsive to all other treatments. The limited availability and high cost of these surgical options place them out of reach for a majority of sufferers.

The economic impact is profound at both micro and macro levels. For the individual, chronic pain leads to absenteeism, reduced work capacity, and, in many cases, job loss. This pushes households deeper into poverty, creating a cycle where inability to afford treatment worsens the condition. For the national economy, the cumulative effect is a significant loss of productive labour hours across key sectors like agriculture and mining. The burden on public healthcare clinics, which manage chronic pain with limited resources, redirects funds and attention from other critical health programmes.

The Path Forward: Integration and Awareness

Addressing the sciatica crisis requires a multi-pronged approach that integrates public health, occupational policy, and clinical care. Primary prevention is paramount, involving public education campaigns on proper lifting techniques, the importance of ergonomics in workplaces, and the management of diabetes. These campaigns must explicitly clarify the connection between diabetes ("shuga") and neuropathic leg pain to combat misinformation.

At a systemic level, investing in telemedicine platforms could connect remote patients with specialists in Harare or Bulawayo for initial consultations, while targeted training for more primary care doctors in musculoskeletal diagnosis could improve front-line care. Occupational health regulations need enforcement and updating to protect workers in high-risk industries.

Ultimately, managing the rising tide of sciatica is not merely a clinical issue but an economic imperative. Without strategic intervention, the condition will continue to erode the health of Zimbabwe’s workforce and constrain economic growth, making it a silent burden the nation can no longer afford to ignore.

Francis

Francis